31 Dec 2011

A few photos from Stoke Newington Gallery

14 Dec 2011

Recent drawings exhibition in Stoke Newington

10 Sept 2011

Swing Night Sketches

4 Sept 2011

Why sketch?

Most people see sketching as a kind of drawing. Not as informal and stream-of-consciousness as doodling, nor as refined as a finished drawing, sketching is a way to work though ideas. It’s a process of exploration and a way to transform a rough notion into something clearly visible to oneself and to others. It allows us to reify concepts so they can be seen, evaluated, and used as the basis for creative decisions.

Nearly everyone is familiar with the idea of sketching. We all know that the car we drive, the building we are sitting in, and the sculpture in the city square probably all started life as a drawing. It’s safe to say that most people have an intuitive understanding of the purpose of sketching and its place in the creative process.

This is because many artistic and design disciplines have well understood sketch languages that underpin the working process. Painting, sculpture, product design, interior design, filmmaking, and architecture all operate with well-defined sketching processes built into their creative decision-making. In each of these disciplines, sketching (and sketches) forms an essential part of the journey from rough idea to finished work. Everyone involved in the process, and even people outside the process, understands the language of the sketch and understands how the sketching process helps to generate better thinking and better outcomes at the end. When people look at a sketch, they know intuitively that they are looking at a sketch and expectations are set accordingly. No one expects more of the sketch than it can deliver.

Sketching is a powerful tool in these situations because it is both a process of thinking and also a way of communicating ideas. It tends to be fast. It can be used to both generate and refine ideas. And when used properly, everyone involved becomes a creative collaborator helping to build a better solution in the end.

But if sketching is such a good way to explore ideas and quickly and efficiently refine thinking, why is it almost the exclusive domain of specific art and design disciplines? There are some design disciplines, such as digital media design, that don’t have a well-defined sketch language. Why is this? And why isn’t sketching more widely understood and used by business managers tackling complex communication, process, and structural problems?

The problem lies with the close association that sketching has with drawing. Although this association is relevant in some cases, creative problems that aren’t naturally resolved or aided through drawing tend not to use sketching as part of the process.

The reason for this is simple: people see sketching as a kind of drawing, not a kind of thinking. If instead we regarded sketching as a kind of thinking then we would possibly see more ways to employ the power of sketching to generate solutions to other kinds of creative problems. Sketching can take many more forms than just drawing.

Now there’s no doubt that drawing is a great way to sketch, and if more people developed the skills and confidence to draw as part of the way they engage with the world, their ability to solve problems and create better solutions would be improved. But the thing that often stands in the way of sketching is not drawing skill – it’s the computer. The computer tricks us into thinking we are sketching, when in actual fact our minds are engaged in the process of using the computer, not articulating the idea.

You can see this played out in some design disciplines. For example, most digital media designers rarely pick up a pencil at any stage in the process. Although there are lots of websites out there that are fantastic experiences and a pleasure to use, there are many, many more which are counter-intuitive expressions of utterly thoughtless design. Graphic designers too tend to draw less and less these days as a part of their process. And where drawing is used, it is often not of a sufficient level of detail and information to be a helpful addition to the process of making decisions.

The reason for this is the tools of the trade. The entire creative process of digital media designers and graphic designers is carried out using the computer. The problem here is that even if a designer thinks he or she is sketching, the second they open up Photoshop or Illustrator they are automatically engaged in the process of making a finished product. The tool leans so heavily in the direction of the finished item that it is impossible for a designer to resist the pleasurable temptation to fiddle with details before the basic idea is even worked out. The rush to the finished product means that ideas remain unexplored and decisions about finishing details wind up being made at the start of the process instead of at the end.

This same problem undermines the creative thinking of business leaders and managers too. People in business are constantly being asked to generate ideas and solutions to complex problems, but because they lack a well understood sketch language, the tendency is to use the most obvious tool – the computer – and do all the thinking there.

Let’s take planning for instance. Planning a complex project should ideally be a sculptural exercise in shaping the right sequence of activity to achieve a goal. Instead it quickly turns into a process of filling in lines on a spreadsheet in Excel or MS Project. In the absence of a sketching process, the tool takes over and all the thinking directed at filling in the spreadsheet, not in solving the challenges of sequencing, interdependencies, and prioritisation. Making a beautiful plan document becomes the aim while the value of the planning conversation via a robust sketching process gets forgotten.

The same holds true for presentations. Everyone in business these days is required at times to communicate complex ideas in a simple and memorable way. Yet, in spite of this creatively challenging brief, sketching as a way to work out what is important and what needs to be said is absent from the process. People jump into PowerPoint before they have even figured out what they want to say. Time is wasted in the beginning on selecting fonts, colours, and bullet styles. Ideas that have no value end up surviving in the final version simply because the author spent significant amounts of energy choosing clip art. And as a result of the absence of a sketching process, people in business routinely suffer the consequences of poorly constructed stories delivered in PowerPoint.

Introducing a sketching moment in the process of creating plans, presentations, structures, technical architectures, business models, etc would force a different mode of thinking in the early part of the process when it is most critical. Sketching should be part of everyone’s skill set in any line of work that requires the ability to solve complex problems where different emotional and logical criteria need to be addressed.

Developing a sketch habit in the early stages of the creation of an idea requires four things to be successful:

- Speed of execution – The sketching process needs to accelerate the generation and refinement of ideas, not slow them down. Tools and techniques need to be lightweight, easy to use, and not dependent on technology or complex operations.

- Clarity that it is a sketch – The tools that are used should not be the same tools to develop the final output. Don’t “sketch” in Excel, PowerPoint, Word, or Photoshop. Sketch in one technology (paper, whiteboard, Post-its) and finish in another. Find ways to share ideas so they clearly communicate that this is a sketch to avoid the temptation to critique a sketch using the criteria of the finished product.

- Answering the right questions – Sketching works well when it understands the questions it is seeking to answer. Don’t try to answer detailed finishing questions in the early sketch process. Keep the sketching focused on the right questions and don’t get off track.

- A process of reflection and review – For sketching to be successful, it needs the author to be involved in a nearly simultaneous process of reflection and review. This means that the process of creating the sketch needs to be ‘plastic’ enough to be changed easily on the fly. Describing one idea in the sketch will change a previous decision and the sketch process needs to be able to respond to this easily.

Sketching is a powerful tool no matter what your discipline. Even if you don’t draw, everyone should sketch.

24 Jul 2011

13 Jul 2011

13.07.11

13.07.11 Front1

59 x 42 cm

ink on paper

13.07.11 Right

27.5 x 20

pen and gesso on paper

13.07.11 Left

38 x 28 cm

ink on paper

13.07.11 Front2

16 x 12.5 cm

pencil on paper

6 Jul 2011

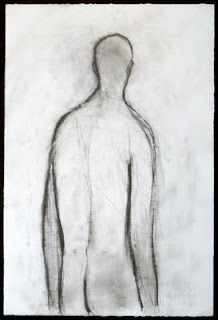

Can a group of people make a good drawing?

The reason for involving other people in the creative and production process is very often due to the simple fact that one person, working on their own, can’t do it all by themselves – either because of the range of skills required or the sheer volume of work. To coordinate the creative effort of teams of people, an organisation needs to be created with reporting lines, decision hierarchies and clear roles and responsibilities. Whether it is the master painter or the film director, these creative processes have someone in charge of the process to ensure quality and consistent adherence to a vision.

But what about the humble drawing? Drawing is largely a solo activity and, as John Berger points out, knowing that drawings are done by individuals, not teams, means when we look at a painting we are reminded of the subject, but when we look at a drawing we are reminded of the artist. However, given that drawing is such an individual creative process, is it possible for a group of artists, working without a clearly defined role structure, to make a coherent and compelling drawing?

Over the last few months I have attended some life drawing classes at the Prince’s Drawing School in Shoreditch, London. www.princesdrawingschool.org In a recent session we did a short exercise where we each drew the model for five minutes. At the end of the five minutes each person moved to the easel to their left and took up the drawing that was already in progress. For the next five minutes we were encouraged to engage with the unfamiliar drawing on its own terms and not be afraid to rub out parts and fix things that we didn’t feel were working. The aim was to try to continue the drawing, but improve it in some way. We carried on doing this every five minutes for about a half an hour, each time making additions and corrections to the different drawings in the circle.

At the end we took a look at the results. Most of the drawings looked as one might expect – a mish-mash of different approaches jumbled together to create something interesting at best, but not terribly beautiful or compelling.

But one drawing stood out from the rest. For some reason, one of the images worked and created an interesting piece that had something clearly special about it. Without discussing it ahead of time, each of us had somehow played to our strengths. The resulting marks, instead of competing against each other, harmonised. This drawing had a sense of coherence and appeal that none of the other images had.

Not only does this image challenge a few assumptions about the nature of drawing as a solo activity, it also raises an interesting question about authorship. If there is no one in charge of the creative process, whose drawing is it? It’s like a fantastic conversation with a group of friends. The conversation itself is the product of the collaborative interaction of the group, but no one person can claim ownership to the output. Like a conversation or a dance with a partner, this drawing is an unspoken interplay of decisions and contributions. Part of its charm lies in the feeling of having made these connections with other people through the mark making process.

29 May 2011

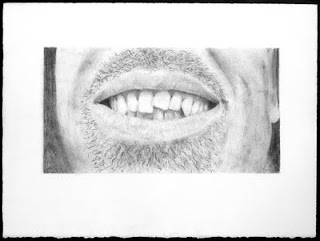

My teeth

28 May 2011

22 May 2011

Is inspiration actually a form of permission?

Visual people tend to find inspiration in the work of other visual people. Walk into the studio of any artist or designer and you will very likely find images, books, objects and other visual odds and ends scattered around the place. Sometimes they can be ordered and organised, but most often they are pinned to the wall, taped to the easel, and sitting on the desk next to the computer.

These things aren’t there by accident. They have been carefully selected and combined into a tapestry of personal inspiration. Selected for their colour, form, size, subject, technique – whatever – artists and designers surround themselves with these inspirational reference items as a matter of habit. This is not about copying; it is about comfort. Having these images and objects close at hand, and occasionally picking them up and looking at them feels good. In some strange way being in the presence of these talismanic objects brings a sense of comfort and security to an endeavour that is often fraught with anxiety and self-doubt.

More than mere decoration – they form a kind of artistic ‘habitat’ that helps to create the conditions for the right kind of conversation with the drawing, painting, etc. In some ways these things are almost more important than the physical aspects of the studio in terms of creating an environment that is conducive to the right kind of creativity. Their presence seems to create an atmosphere that supports the creative process. They are without a doubt an explicit source of inspiration. But that's not all.

In addition to the inspiration that comes from these images and objects, I also think that these things confer a kind of ‘permission’ to the artist or designer. Because these things are very often infused with a particular kind of energy, and very often a particular kind of authorial commitment (even if that author is Mother Nature) they do more than simply inspire. These images and objects act as indicators that there are other people in the world who think a bit like you do.

Why is this so important in a field of endeavour that is fundamentally attached to the notion of free will and independent creative invention? Starting with the Renaissance, and since the early twentieth century in particular, the practice of western artists and designers has become increasingly driven by the myth of the lone genius. Working in complete isolation in order to have a pure, unadulterated idea has become an unspoken artistic ambition. This kind of isolation is a very uncomfortable place for all but a tiny fraction of people engaged in creative work. Everyone needs inspiration, but I suspect that many people need something more as well.

My hunch is that the tendency to surround oneself with carefully selected images and objects is partly about providing inspiration, but also about providing permission from across time and geography at just the moment it is needed. When stepping into the uncharted waters outside ones creative comfort zone it is helpful to have not just a sense of inspiration, but a sense of support and acceptance. It is energising to know that in that moment there are people (whom you have never met) who can provide silent encouragement for acts of personal artistic bravery. I believe that studios around the world (including my own) are effectively ‘wallpapered’ not with pieces of inspiration, but with words of encouragement.

20 May 2011

17 May 2011

14 May 2011

8 May 2011

Philly sink

This drawing, done in 1995, is of our sink where we washed and brushed our teeth every day for the 5 years we lived there.

When are we?

pen on paper

pencil on paper

99 People I Never Met

pen on paper

7 May 2011

Three (unrelated) drawings

ink and wash on paper

charcoal on paper

pen on paper